by Phillip J. Wajda

It's unusually quiet on campus as another academic year winds down. The day before, 350 graduating seniors and their families filled the College grounds for Union’s 176th Commencement.

But now the campus is nearly empty. As night falls on this pleasant Sunday on the thirteenth of June 1971, two men sneak over to a rear window on the ground floor of the Schaffer Library’s east side.

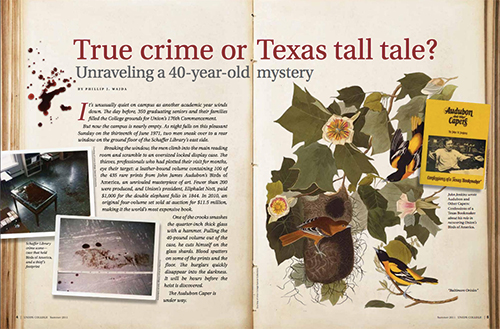

Breaking the window, the men climb into the main reading room and scramble to an oversized locked display case. The thieves, professionals who had plotted their visit for months, eye their target: a leather-bound volume containing 100 of the 435 rare prints from John James Audubon’s "Birds of America," an unrivaled masterpiece of art. Fewer than 200 were produced, and Union’s president, Eliphalet Nott, paid $1,000 for the double elephant folio in 1844. In 2010, an original four-volume set sold at auction for $11.5 million, making it the world’s most expensive book.

One of the crooks smashes the quarter-inch thick glass with a hammer. Pulling the 40-pound volume out of the case, he cuts himself on the glass shards. Blood spatters on some of the prints and the floor. The burglars quickly disappear into the darkness. It will be hours before the heist is discovered. The Audubon Caper is underway.

For 40 years, “The Audubon Caper” has been one of the College’s greatest mysteries. A few weeks after the theft, John Holmes Jenkins III, a prominent rare book dealer and publisher from Austin, Texas, contacted authorities to report that he had been approached by a man looking to sell “pictures of birds” that were discovered in an attic. Working with the FBI, Jenkins flew to New York to meet with the seller, a longtime criminal from Pennsylvania. After a harrowing sting operation, the plates were recovered in a Queens motel.

The recovery attracted national media attention, including The New York Times, network news programs and later, Sports Illustrated. Lauded as a hero, Jenkins collected a $2,000 reward from Union, which he promptly returned to create a bibliography award in his name. Later, the College awarded him its Founders Medal and an honorary degree. He also served briefly as a member of the board of trustees.

Jenkins wrote an entertaining account of his adventures for a collection of essays, "Audubon and Other Capers: Confessions of a Texas Bookmaker," which has served as the primary source about the recovery. He thrived on sharing the story of his heroic deed, admitting “it gets a little better each time I tell it.”

Yet in each retelling, a number of troubling questions linger. Who was behind the theft? Why was the College targeted? What happened to the thieves? And most troubling, did Jenkins, a brilliant yet shameless self-promoter, grossly misrepresent his role?

Now, four decades later, a broader picture has emerged about the daring heist, culled from scores of interviews with friends and associates of Jenkins, former Union employees, court records and newly uncovered material from the College’s archives.

For the first time, the theft has been traced to a long-dead shady book dealer from New York who had done business with the College a decade earlier. New evidence suggests that the book dealer conspired with a ring of thieves from the Philadelphia area to steal Union’s Audubons and offer them to Jenkins. The inside story is also bolstered by one of the thieves, now 78, whose account threatens to shatter long-held assumptions about the crime, including whether Jenkins’s role was entirely heroic.

Yet some questions may never be answered. Many of the principal players are dead, most notably Jenkins. In 1989, his body was found floating in the Colorado River outside Austin. He had a bullet wound in the back of his head. How he died remains a mystery.

In addition, the FBI has denied repeated Freedom of Information requests about the theft or Jenkins, making it difficult to pinpoint the late Texan’s exact role with the bureau. These obstacles and other twists only add intrigue to a case that former Texas congressman J.J. Pickle once described as a “tale that rivals any detective author’s imagination.”

Summer 1961.

For decades, Union has served as a federal depository library for thousands of government documents, from the official report on the attack at Pearl Harbor to pedestrian pieces like Zip Code directories and Statistical Abstracts of the United States.

The collection grew quite large, with many of the documents stored on the library’s unheated third floor of the Nott Memorial. As plans were finalized to move the library into a new building across from the Nott, the collection must be thinned out.

While many book sellers consider government documents to be of limited value, James Rizek was an exception. A former theological student, Rizek operated the Raritan Book Company, near Rutgers University in New Brunswick, N.J.

When Rizek learned of Union’s dilemma, he offered to find a home for some of the College’s surplus. In return, he arranged for the library to acquire portions of the New York Times on microfilm, a deal worth several thousand dollars. Union’s librarian, Helmer Webb, close to retirement and under pressure to clear out the third floor before leaving, took Rizek up on his offer.

Rizek arrived on campus with a truck and some workers to help remove boxes. He also brought personal baggage. In 1957, while running The Jabberwock, a record store in central New Jersey with his brother, Ernest, Rizek had orchestrated a Ponzi scheme that netted him as much as a half-million dollars.

Having avoided jail for that scheme, Rizek turned his attention to books, with a particular focus on microfilming rare periodicals and documents for libraries. But he didn’t abandon his thirst for the con. In early 1961, Rizek conspired with the head of the Scranton Public Library to remove hundreds of books and documents from the Pennsylvania library to resell.

While looting Scranton’s library, Rizek began removing thousands of Union’s government holdings. No one had reason to be suspicious of Rizek, although his presence on campus made Ruth Anne Evans, the longtime associate librarian, uncomfortable. And with good reason. As Walter Goldwater, a deceased antiquarian book dealer in New York City later remarked: “Rizick (sic) was, of all the people we knew in the book business, probably the most crooked. If he had been able to make more money being honest than dishonest, he still wouldn’t have done it.”

By the time Webb retired in 1962, Rizek’s trips to campus had ended. Though Rizek’s association with Union was over, the brief relationship provided him with valuable knowledge: a familiarity with the campus and an awareness of the library’s most prized possession: Audubon’s "Birds of America."

U.S Penitentiary, Lewisburg, Pa. 1969-70.

Following a lengthy appeal, Rizek began serving a two-year sentence in December for his Scranton scheme. Both Webb and his Schaffer Library successor, Edwin Tolan, testified at the trial about the deal with Rizek for the Times on microfilm. In return, they said, “4,594 books and periodicals were shipped by Rizek to the Scranton Public Library.” There was no evidence the material ever arrived.

Meanwhile, a rough Jewish street gang from Philadelphia spent much of the 1960s engaging in armed robberies, arson and assaults. One of the crooks was Kenneth Paull. He, along with his good friend, Allen Rosenberg, worked for a time with Sylvan Scolnick, better known as Cherry Hill Fats, a notorious 600-pound crook with ties to organized crime.

Among the gang’s jobs was a bizarre heist in which they helped steal $100,000 from a Philadelphia bank. The money, believed to be proceeds from earlier crimes, was in a safe deposit box rented to another associate.

The men went to the bank to retrieve the box. As one tossed a rock through the bank’s front window as a diversion, Paull began shouting, “It’s a bomb. It’s a bomb. Everybody get down,” according to Allen M. Hornblum's book, "Confessions of a Second Story Man: Junior Kripplebauer and the K&A Gang." Rosenberg then rushed into the bank’s vault and snatched the safe deposit box.

Paull and Rosenberg eventually confessed to the bank heist and were each sentenced to three to 20 years in federal prison. Rosenberg was sent to Lewisburg, 170 miles west of Philadelphia. It was during this prison stint that the South Philadelphia native whose crew used guns, threats of violence and other forms of intimidation, crossed paths with Rizek, the smooth-talking businessman-turned-con man from Brooklyn.

Rizek offered Rosenberg some criminal advice.

“Why go in and steal diamonds and stuff like that when you can make more money stealing art,” he told him. “It’s a whole lot easier.”

Rizek walked out of Lewisburg on Aug. 3, 1970; Rosenberg followed on Halloween. Eight months later, Rizek pointed Rosenberg toward Schenectady.

June 12, 1971.

It’s a warm and sunny Saturday for Commencement. It had been an unsettling year, and political unrest over the Vietnam War swept the campus. As fears of a violent protest swelled, President Harold Martin ordered all academic buildings, including Schaffer Library, locked for the weekend.

While the threat of violence created an uneasy tension, Commencement also generated a bit of buzz due to the speaker, Hungarian author Ivan Boldizsar. It was the height of the Cold War, and Boldizsar was thought to be the first representative of the Soviet bloc to receive an honorary degree from an American college since World War II.

“It took a lot of courage for Union College to ask a man from a communist country to come here and deliver the Commencement address,” Boldizsar told the New York Times.

During the ceremony, a scuffle broke out when protesters interrupted speeches and waved a Viet Cong flag. A young professor leapt from his seat in Library Plaza and seized the flag. Security moved in to quiet the chaos. A photo of the incident would appear in newspapers around the country.

Typically, one of the four volumes holding the Audubon plates was on display during Commencement weekend. But with the library now locked, only those who visited before the doors shut Friday night were able to see the glorious volume opened to Plate 79: the Eastern Kingbird, or Tyrant flycatcher.

Monday, June 14, 1971.

As the excitement of Commencement faded, the campus began to settle into its languid summer routine. But the laid-back mood was shattered when a secretary in the library who arrived early called Ruth Anne Evans, the associate librarian, at home. There was a note of panic in her voice.

“What was on display in the case in the reading room?” the woman asked Evans.

“The First volume of Audubon’s Birds, ’ Evans said as a sick feeling settled in her stomach. “And why are you using the past tense?”

Word of the crime spread quickly. English Professor Carl Niemeyer stopped by the faculty lounge in the Humanities building. He overheard two colleagues discussing a burglary.

“Haven’t you heard?” one asked Niemeyer. “They’ve stolen the Audubons.”

“There’s blood everywhere,” said another.

Niemeyer headed to the library. Schenectady Police were surveying the crime scene. The FBI was notified. Calls were made to local hospitals to check if anyone had sought treatment for cuts to their hands or arms. Some speculated the theft was tied to the demonstrators at Commencement. A member of the library staff walked along the campus creek, believing the volume may have been dumped there as a sign of anti-establishment protest that spun out of control.

Library staff members sent letters to rare book dealers across the country and Canada, seeking clues. An ad offering a $2,000 reward was placed in the Antiquarian Bookman, known as the AB to legions of book dealers, collectors and librarians. But as the days passed, it appeared the College’s cherished Audubon plates would be lost.

In early July, Evans attended a meeting at the Schenectady Museum, just a few blocks from campus. When it ended, someone asked her to contact the College library immediately. The secretary told Evans that a book dealer in Texas had seen the ad and left a number for her to call.

Evans rushed back to campus and dialed the number.

“Hello. This is John Jenkins.”

July 8, 1971.

Jenkins, 31, was at work in his enormous office at the Jenkins Company on Interstate 35 on the edge of Austin when a well-dressed tall, husky man arrived for an appointment.

Jenkins described the encounter in a tense and often theatrical account in Audubon and Other Capers.

The man, who gave his name as Carl Hoffman, pulled out a rare 16th century Persian manuscript of the Koran. He told Jenkins he had other valuable materials to show him later.

Jenkins grew suspicious. He had seen the notice in the Antiquarian Bookman (AB) about the College’s stolen prints and the theft of rare books from a dealer in New York City the previous week. He followed a hunch.

“Do you have any old American prints of animals or birds?”

“I have some big old color prints of birds,” Hoffman replied.

“Would they be someone like Audubon?”

“Yes. I have about a hundred of them,” Hoffman said.

The men agreed to meet again in a week.

Jenkins immediately contacted the Union library to share his suspicion that Hoffman had the College’s stolen prints. “It will be a pleasure to help further in the apprehension of these scoundrels,” Jenkins wrote the next day to Ed Tolan, the librarian.

Jenkins then notified the FBI.

July 14, 1971.

Working with the feds, Jenkins arranged to meet Hoffman in New York City to examine the Audubons. Hoffman picked up Jenkins at JFK Airport and drove him to the Jade East Motel nearby. Here, scattered on the bed in Room 209, were some of the Audubon prints and other rare books. Jenkins (and the FBI) never realized it, but waiting in the room next door were Allen Rosenberg and the accomplice who snatched the plates from Union’s library.

Jenkins offered Hoffman $50,000 for the lot, but told him he needed to return to his hotel to contact his banker in Austin. Instead, Jenkins alerted the FBI, who had the two men under surveillance.

Federal agents soon descended on Hoffman’s room and he was arrested without incident. The Audubon prints were recovered in the trunk of Hoffman’s car. The cover page was missing. Several of the plates were badly torn from being ripped from their binding; a half-dozen of the prints had bloodstains on them. Remarkably, though, the set was complete. Authorities also found some of the rare books taken in the New York City robbery and two loaded pistols.

“Stolen Audubon Prints Found in Queens Motel,” read the headline in the next day’s New York Times.

Back at his hotel that night, Jenkins excitably composed a 3 1⁄2-page letter to Tolan “while the events were still fresh on my mind.” While some details didn’t mesh with the breathless version he wrote for “The Audubon Caper” a few years later, Jenkins described a “bizarre and frightening, albeit exhilarating, day for this young bookman.” He also made a claim for the $2,000 reward, directing Tolan to use the money to create an annual fellowship for bibliographical research.

College President Harold C. Martin thanked Jenkins for his heroic role.

“The episode of recovery, as you note, has all the earmarks of a thriller except for the lack of a foreign setting, more in the style of Eric Ambler perhaps than in that of John McDonald,” Martin wrote. He also wrote to J. Edgar Hoover, director of the FBI, to express his gratitude for their assistance.

Meanwhile, Hoffman was arrested on a charge of interstate transportation of stolen property. He told authorities his name was John Galt from Burlington, Vt. He showed up for his arraignment wearing cowboy boots, an orange cowboy shirt, and a red and gold tie. But the charge didn’t stick because officials said they couldn’t prove Hoffman took the stolen plates across state lines; instead, he was returned to Pennsylvania on a parole violation.

The real name of the suspect also emerged: Hoffman was really Kenneth M. Paull of Philadelphia. He had been paroled in May for the bank box robbery.

The plot to steal Union’s Audubons had been years in the making, beginning when James Rizek eyed the prints while on campus in the early 1960s. The idea took hold nearly a decade later when Rizek shared a federal prison address with Allen Rosenberg.

Now, in the Metropolitan Correctional Center, only Paull’s name was attached to the crime. It remained that way for decades.

A different perspective

Kenneth Paull is now 78. Much of his adult life was spent as a criminal. In 1963, he pleaded guilty to causing a bomb scare after telling an airline employee his luggage on a Detroit bound flight contained explosives. And in 1993, he was one of 10 people charged in a plot to illegally wire $50 million from a New York bank to another in Philadelphia. In between, he did stints for robbery, assault, arson and other crimes.

The Audubon heist, he said, was the only time he dabbled in stolen artwork. He was reluctant to talk at first.

“The last thing I’m looking for at this stage of my life is publicity,” he said by phone from his home outside Philadelphia.

The heist was half a lifetime ago for Paull and he was unable to recall key details. Also, Paull’s version of events cannot be corroborated because many of the principal figures are dead, including Rizek, Rosenberg and of course, Jenkins. But through a series of conversations, Paull provided a fascinating account of the Audubon affair, the first from a perspective other than Jenkins’s.

A book dealer from New York (he described Rizek, though Paull couldn’t remember his name) reached out to a prison pal, Rosenberg, and told him he had a customer who wanted the Audubons. Rosenberg and at least one other person came to campus to steal the prints. Paull insisted it wasn’t him, and in an apparent nod to a code of honor among thieves, said he didn’t want to uncover the name of the person, who might still be alive.

The burglars expected a hefty payday, with Rizek collecting a nominal fee for pointing the criminals to Union and for finding the buyer because, as Paull said, “I didn’t know an Audubon from a Schmaudubon.”

“The fellas who were involved wouldn’t have moved anything for less than $50,000,” Paull said. “ They wouldn’t have even gotten out of bed. It just wasn’t worth it to them.”

The customer, who, it turned out, was Jenkins, was originally going to New York to retrieve the plates, Rizek told the thieves. But for some reason, Jenkins refused to travel. And Rizek begged off to going to Texas, telling the thieves he was on parole and was “being watched.” So Paull, a former pharmacy student who was considered the brains of his gang, went to Texas to close the deal.

Dealers routinely buy and sell with each other in the competitive and sometimes shady rare book world. Jenkins had bought part of an Albany, N.Y., bookseller’s estate from Rizek in 1969. The rumor among some dealers was that Jenkins felt cheated on the sale, but there had never been any evidence to suggest their dealings were criminal.

Yet in a stunning revelation, which, if correct, seriously undermines Jenkins’s Audubon tale, Paull said the only reason his associates’ stole the prints was because Rizek told them he had a customer for them: John Jenkins.

“Oh absolutely. Absolutely,” Paull said when pressed on the critical part of whether Jenkins was aware the prints he had allegedly requested from Rizek were stolen. “I was a professional thief. Do you honestly think I just flew down to Texas and looked around for somebody to buy stolen goods? We didn’t do anything on spec. We had a customer.”

No one can say with certainty that the connection between Jenkins and Rizek turned criminal. It’s conceivable that Rizek, who could not be trusted, concealed from Jenkins the fact that the Audubons were stolen. As a detective once noted, Rizek was “a terrific salesman who could sell City Hall to the mayor.” Rizek also could have deceived Paull and his associates by having them pretend the deal with Jenkins was legitimate.

Paull doesn’t buy that.

“I don’t like to say this, but (Jenkins) was a blatant liar. He was a thief, just like I was.”

Michael Ginsburg, a longtime book dealer in Sharon, Mass., worked with both Rizek and Jenkins. Rizek, he said, was the “consummate con man.” He doubts Rizek would have shared with Jenkins the devious circumstances of the acquisition of Union’s bird prints.

“That would have been the death knell,” said Ginsburg. “Ninety-nine percent of the people in this business wouldn’t touch a stolen book with a 10-foot pole because your reputation would be ruined forever. If Rizek was trying to hustle you, he would tell you he just bought it from a collection. The last thing he would say is, ‘I have some stolen books to sell you.’”

When told of Paull’s assertion that her late husband knowingly planned to buy stolen material, Jenkins’s widow’s first reaction was “Really? That’s interesting.” She quickly dismissed the possibility, though.

“It doesn’t hold water,” Maureen Jenkins said by telephone from her home in Austin, where she still lives. “If someone had a set of Audubons and was looking for a book dealer to take them, Johnny would have been one of the dealers who would be called,” she said. “And we would say, ‘Sure, let us see them,’ not knowing if they were stolen.”

Besides, she said, if the Jenkins Company was looking to make an expensive purchase like the Audubon plates, they would need to have a customer lined up for a resale.

“And I would have known about it,” she said. “We certainly didn’t have the money to take out and let them (prints) sit.”

So if Paull is correct, why would Jenkins tip off the FBI? Theories abound, though none of them is without its flaws. Maybe Jenkins, who expected to do business primarily with Rizek, got spooked when professional thieves took control of the deal. Or perhaps after learning from the AB that some prints may have had blood stains on them, Jenkins wanted no part of damaged goods. All of these theories, however, require one to assume that if Jenkins had something to hide, he was willing to gamble that the FBI would not discover it.

Paull has his own theory. He believes Jenkins was in trouble with the FBI on other matters and cut a deal to “buy his way out.”

Regardless, Paull said that when he saw the FBI agents swarm his motel room that July day in 1971, he knew he had been set up.

“I should have smelled a rat,” he said. Paull had never read Audubon and Other Capers until Union sent him a copy.

“Greatest fantasy I ever read,” Paull said. “I read Edgar Allen Poe. I was flabbergasted as I read his version of what occurred. And what’s more flabbergasting is the federal government went for it. They actually believed it.”

He particularly enjoyed the fact that the whole affair became the basis for an episode of "Kojak."

“I used to watch Kojak, but I wouldn’t have recognized that episode because none of the things that were in the article had anything to do with what really happened.”

His reputation soars

After the recovery of the Audubons, Jenkins’s profile soared. He was cited for bravery on the floor of Congress and gave countless media interviews about his adventure.

He visited campus in June 1973 to receive the Founders Medal, giving a talk he promoted as the “true” story of the Audubon recovery. That same weekend, the first John H. Jenkins Prize for Bibliography, created with the reward money he collected, was presented to G. Thomas Tanselle, an English professor from the University of Wisconsin (The prize was discontinued in 1981 for lack of funds).

Jenkins also donated a copy of his 1965 book, "Audubon and Texas," to the College, with the inscription: “In remembrance of my exciting week on the ‘Audubon Caper.’”

Jenkins and his wife, returned to Schenectady in 1976, when he was presented with an honorary degree at Commencement for his “high standard of integrity in business, intellectual contributions, and activities in the world of literature and scholarship.” In between, he published "Audubon and Other Capers." Few believed his account was purely nonfiction. "The Encyclopedia of Union College History" called Jenkins’s version “reasonably accurate.” But determining which parts were true proved to be a challenge.

“Johnny was a storyteller,” Maureen Jenkins said. “He liked a good tale.”

In 1975, he scored a coup by spending millions to acquire a large collection of Americana from Edward Eberstadt and sons of New York City.

The Antiquarian Booksellers’ Association of America (ABAA) named Jenkins its first security officer. Later, he became president of the organization, producing a 28-page primer, "Rare Books and Manuscript Thefts: A Security System for Librarians, Booksellers and Collectors." Among the chapters: “The Nature of the Book Thief”, “What to Do if You Suffer a Book Theft” and “What to Do When the Thief is Caught.”

“Everyone in the book world has—both morally and legally—the obligation to prevent theft, and to make thefts known when they occur,” Jenkins wrote.

Wearing a Stetson and chomping on a cigar, Jenkins also achieved a bit of notoriety at the poker table, competing in major tournaments in Las Vegas and elsewhere. His poker buddies, who included the legendary Doyle Brunson, tagged him with the nickname “Austin Squatty,” because of his short frame and the way he sat cross-legged at competitions.

But then his reputation soured. A series of res at his warehouses destroyed thousands of valuable books and documents. Authorities suspected him of arson in the last one in September 1987 and he was rumored to be on the verge of being indicted when he died.

“He was not an honest person,” said Jennifer Larson, a longtime book dealer and former chair of the ethics committee of the ABAA.

She was hired by the insurance company to appraise Jenkins’s collection after the 1987 fire. “He was very smart and very charming, but he always thought he could get away with whatever he could,” said Larson.

No episode was more damaging to his reputation than when Jenkins was suspected of selling forgeries of Texas Revolution letters and broadsides. Tom Taylor was a dealer and printer in Austin who in the 1980s became suspicious of the plethora of rare historical documents in the marketplace. He eventually discovered that many were fakes and traced their provenance primarily to three dealers. One of them was Jenkins.

Jenkins insisted he was unaware he was selling fakes, but the scandal and the ensuing publicity were bad for business. Taylor subsequently wrote a celebrated book on his research, "Texfake: An Account of the theft and Forgery of Early Texas Printed Documents," in which he skillfully presented his findings.

“You can willfully disregard evidence if you want to be a loyalist to Johnny Jenkins and say that Tom Taylor never said Jenkins sold forgeries,” Taylor told me. “I certainly did. I just didn’t say it in so many words.”

And today?

“I’m quite certain that Johnny knew those documents he was selling were forgeries.”

April 16, 1989

Jenkins left his house around 12:30 p.m. to conduct research on his next book. Hours later, a fisherman spotted his body floating in the Colorado River in Bastrop County, Texas. His wallet was stripped of credit cards and cash, and his Rolex watch was missing. Parked nearby in the remote area was his gold Mercedes. The passenger door was wide open and the left-rear tire was flat. Jenkins had a wound in the back of his head, made with a large-caliber gun.

“Book Dealer’s Life Read like a Best Seller,” read the headline in the Austin American-Statesman.

A justice of the peace (now deceased) ruled it a homicide, in part due to the path of the bullet and because no weapon was found.

Family and friends believed Jenkins, who often carried large amounts of cash, may have been killed during a robbery. There were even whispers that those involved in the Audubon theft may have been responsible.

The sheriff, Con Kiersey, called it a suicide, angering Maureen Jenkins and many of her husband’s supporters. Stories had spread that Jenkins once described to friends how to commit the perfect suicide by making it appear like a murder so someone could collect the insurance. Indeed, two years earlier, Jenkins had purchased a policy worth more than $1 million.

Kiersey, who spent years investigating homicides for the Austin Police Department, said evidence at the scene didn’t support a homicide. He also said the turmoil in Jenkins’ personal life—the fires, the forgeries, the several hundred thousand dollars in debt for gambling and failed business dealings—pointed to suicide.

Kiersey, now in his 80s, stands by his ruling.

“He enjoyed the limelight and was considered an expert, and now all of sudden it comes crashing down,” Kiersey told me. “His world was closing in on him. He was in trouble up to his ears with the IRS and everybody else. If people really thought it was a homicide, they’d be hollerin’ their heads off, saying we got to open a cold case. No one’s ever said anything.”

Questions remain

Through the years, people have formed passionate opinions on the controversial aspects of Jenkins’s life, such as whether he was responsible for the fires at his warehouse and knowingly sold forgeries, and how he died.

“There are so many stories out there about Johnny,” said Maureen Jenkins, who met her future husband on a blind date in October 1961 and married him the following year. “I have heard them all.”

So what do others think when they’re asked to consider the disturbing possibility offered by Paull that Jenkins turned an insidious role into a heroic one in the “Audubon Caper.”

“The notion of him doing anything devious and criminal is just ridiculous, totally ridiculous,” said Michael Parrish, who worked for Jenkins and is now a history professor at Baylor University in Waco, Texas. “He loved the limelight and he loved to make deals, but he was never the kind of guy who operated in a devious way.”

The award-winning writer Larry McMurtry ("Lonesome Dove," "Terms of Endearment") didn’t care for Jenkins. In the foreword to "Texfake," McMurtry referred to Jenkins as a “frontier snake-oil salesman.” Still, McMurtry said he doesn’t think Jenkins played a sinister role in the Audubon theft.

“He had too much to risk,” said McMurtry, who has owned antiquarian bookstores in Texas, New York and Washington, D.C. “He could not have an Audubon stolen on order and then sell it. That would have been impossible.”

Kevin MacDonnell managed the literature section of the Jenkins Company from 1980 to 1986. He considered his boss a friend and mentor, but the notion that Jenkins may have misrepresented his role in the Audubon theft doesn’t surprise him. He behaved the same way when the forgery scandal erupted, MacDonnell said.

“John was good at covering his tracks,” said MacDonnell, who has been in the rare book business in Austin for more than 40 years. “He liked to put on the white hat and pretend to be helping, when all he was doing was hiding his culpability.”

When she first read "Audubon and Other Capers" years ago, Jennifer Larson thought it was “self-puffery.” With the benefit of hindsight— given the cloud that settled on Jenkins for the forgeries, fires and other possible misdeeds— her view of the “Caper” has become more jaded.

“I’m firmly convinced he was capable of being involved,” Larson said.

As for Paull, he stopped talking after a series of conversations for this article over many months.

“I have no problem discussing this with you, but what can be accomplished at this point?” he said.

In his brilliant and exhaustive profile in the New Yorker shortly after Jenkins’s death in 1989, Calvin Trillin wrote: “Over the years, colleagues watched the story of how Jenkins turned in the Audubon-folio thieves swell from a fairly straight-forward bust after a meeting at a motel ... to a bullet-sprayed, blood-splattered adventure.”

He included the inscription Jenkins wrote in a copy of "Audubon and Other Capers," to one reader:

“The whole truth, and nothing but the truth—as I remember it.”

The title of Trillin’s piece? “Knowing Johnny Jenkins.”

Forty years after the Audubon theft, we are finally starting to figure him out.