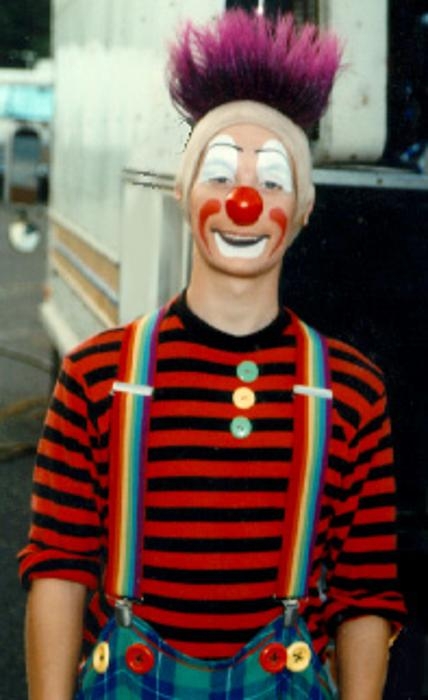

There’s a clown in Steinmetz Hall. Insert punchline here.

Long before he started pontificating about evolutionary fabrication, artificial intelligence and robotics, John Rieffel entertained thousands as a professional circus clown.

The assistant professor of computer science got his big break during his senior year of high school when Ringling Brothers and Barnum and Bailey Circus held an open audition in his hometown of Washington, D.C.

A geek by his own admission who dabbled in theater and juggling, Rieffel was encouraged to try out by a friend who had been accepted into Ringling’s famed Clown College in Baraboo, Wis., a year earlier.

“John, you have to do this,” the friend told him. “You are cut out for this. You are the kind of person they want.”

On a whim, Rieffel joined dozens of other amateur performers hoping for a spot under the Big Top. Some applicants did standup for the 30-second portion of the audition. Others juggled. Rieffel had prepared nothing.

“I can tell jokes, but you have seen that today,” he told organizers. “I can juggle, but you have seen that too. But what you probably haven’t seen is, I can do an excellent handstand.”

It was the ugliest handstand ever. But Rieffel acted like he nailed it. His skit left an impression though, because he eventually received a call from legendary circus clown Steve “T.J. Tatters” Smith, the director of Ringling’s Clown College. Smith asked why Rieffel hadn’t completed the official eight-page application after his audition.

“The most famous clown in the country is calling me to tell me to submit an application?” Rieffel recalled. “So I did.”

A few weeks later, an envelope filled with glitter arrived at the Rieffel house. He had landed a coveted spot in Clown College.

“It was like getting the Golden Ticket from Willy Wonka,” he said.

Rieffel had already been accepted to Swarthmore College, one of the top liberal arts schools in the country. His parents on board, he called the dean, who allowed him to defer admission for a year.

“Three thousand people applied for Clown College every year,” Rieffel said. “Only 30 get accepted. They were more selective than Swarthmore.”

So in October 1994, he headed to Wisconsin for an eight-week boot camp to learn the art of clowning through intense, demanding classes focused on character development, athletics, and physical and verbal comedy.

“It was the hardest work I’ve ever done in my life,” he said. “You have to work hard to make it look easy. You have to work even harder to make it look fun.”

At the end of the tryout, Rieffel wasn’t offered a job in the circus. So he moved back home, juggling jobs as a chimney sweep, a bricklayer and even a salesman in a juggling store, to earn money.

That December, he heard that the Clyde Beatty-Cole Bros. Circus, at the time the largest three-ring tented circus in the country, was looking for performers. He applied, was accepted and in February 1995, went to the circus’s headquarters in DeLand, Fla. to train.

He traveled all over the East Coast, doing two shows a day (three on weekends) seven days a week. He shared a 4-foot by 8-foot room in the back of a tractor trailer with another performer, a space so tight “neither of us could stand up at the same time.”

It was exhausting work, especially for the clown-like wages of a couple hundred dollars a month. Rieffel signed a one-year contract, but after a few months, he’d had enough. He ran away from the circus, enrolled at Swarthmore and continued on an academic path that brought him to Union in September 2009.

When he applied for a position in the Computer Science Department, he didn’t mention his bachelor of funny arts from Clown College. But the chair at the time, Valerie Barr, poked around the Internet and discovered Rieffel’s unusual past.

There would now be a clown among the more than 220 faculty. Ba dum.

Rieffel has no regrets about not sticking with the circus. He now lists his time at Clown College on his professional CV. He also continues to tap into the skills that helped land him a job as a clown.

“Keeping a classroom full of college students engaged and interested in the material is even harder than a stadium full of people at the circus,” said Rieffel, caretaker of Union’s impressive 3-D printer.

He continues to juggle, especially for his seven-year-old son and four-year-old daughter. His time as a professional clown, though, remains locked in a steamer trunk where it all began, at his parents’ home in D.C.

“Being a clown is a lot more complicated than people think,” he said. “It’s a lot harder than people think, and it’s a lot more dangerous than people think. It was something I’ll never forget.”