The letter is short and sincere.

Writing in cursive using blue ink on tracing paper, the Union alumnus offers a small contribution to the annual fund.

He recounts the cities he has lived in the brief time since graduating college. Lubbock, Texas. Newburgh, N.Y. Spokane, Wash.

The letter, sent from England Air Force Base in Alexandria, La., ends with a simple request: please forward the College’s monthly newsletter to a temporary address for the next year so the alumnus can keep up on campus happenings.

He was headed to Vietnam.

Dated Feb. 11, 1968, the letter would be one of the last written by 2nd Lt. David Hugh Whitehill ’66.

Three months after contacting his alma mater, on May 23, 1968, Whitehill was killed. He was one of 2,415 casualties that May, the most for a single month during the war.

A skillful pilot, Whitehill died when his A-37 fighter jet crashed after it was struck by ground fire while he was protecting a flight of C-123 aircraft. He was 23.

His letter, tucked into a campus file filled with notes, news clippings and photos chronicling Whitehill’s time at Union and beyond, is a stark reminder of how a young man’s promising life would tragically pivot.

The letter is also an invitation to honor the service this Veterans Day of Whitehill and the thousands of Union’s alumni, both living and dead, with military experience.

Whitehill arrived at Union from Newburgh, N.Y., the oldest of Walter and Mary Whitehill’s four children. His siblings included Walter, Joan and Brian. His yearbook photo depicts a boyishly handsome fair-skinned student with a mop of blonde hair.

Activities included lacrosse, golf and the ski team.

“He was just a terrific guy. We hit it off immediately,” said Jerol “Jerry” Kent ’66 of East Amherst, N.Y.

The two were roommates and best friends during their four years together. Mathematics majors, they shared an interest in computer programming, then in its infancy. They also joined Kappa Alpha fraternity.

“He was so handsome, he had girls falling all over him, which I did not,” Kent joked. “He also had a terrific sense of humor. He was very popular.”

Whitehill wanted to be a commercial pilot. While at Union, he enlisted in an Air Force Reserve Officer Training Corps program. At the Class of 1966 commencement, he was officially commissioned as a second lieutenant.

An alumni questionnaire he completed stated that “with the many drawbacks of military service, this is, however, one of the best means of gaining flying experience for a future airlines job.”

Following graduation, Whitehill went to Reese Air Force Base in Lubbock, Texas, for a year of military pilot training. He ranked second in his class.

“He was very good at what he did,” said retired Air Force Lt. Col. Bredette “B.C.” Thomas, a classmate.

“David was my first friend there. We learned to fly together. We played sports. He was such a great guy. There wasn’t anybody who didn’t like David.”

Whitehill spent a month at U.S. Air Force Survival School in Spokane and then went to Alexandria, La., for additional training. There, he graduated at the top of his class.

Thomas saw his classmate for the last time when both were in Spokane.

“He came to my room and I said goodbye to him. We had a really nice talk.”

Before leaving for Vietnam, Whitehill met Kent for lunch in Manhattan, where his former college roommate was in graduate school at New York University.

The two discussed the danger awaiting Whitehill.

“He assured me things were going to be fine,” Kent said.

As the two parted, Kent watched his friend walk up the block and disappear around the corner.

“I thought, ‘Is this it?’ I didn’t know.”

On April 16, 1968, Whitehill reported for his assignment to the 604th Air Commando Squadron at Bien Hoa Air Base, Vietnam.

A month later, Thomas was stationed at Kincheloe Air Force Base in Michigan. He was assembling a baby crib. His wife was pregnant with their first child. A pilot-training classmate called with news of Whitehill’s death.

“I just burst out crying,” said Thomas, who lives in Foster City, Calif. “That was the beginning of my understanding the harsh reality of the Vietnam War.”

It took a couple of weeks for Whitehill’s remains to arrive back in the States. He was buried June 5, the same day U.S. Sen. Robert Kennedy was assassinated.

Kent didn’t attend his best friend’s funeral. He wasn’t notified of the death because Whitehill’s parents apparently didn’t know where he lived. When Kent visited Whitehill’s mother later, she showed him the official letter sent by one U.S. senator to next of kin honoring a military death. It was signed by Kennedy.

Whitehill’s brother, Walter, still lives in the Newburgh neighborhood where he and his siblings grew up.

Now 67, he remembers the family driving down to LaGuardia Airport to see David off before his tour of Vietnam.

He recalls his mother wondering if it were the last time they would see him.

Walter was a senior in high school when his aunt showed up at the school to tell him his big brother had died. Recalling that day nearly half a century ago, he started to sob.

“It was such a total shock.”

His parents, particularly his mother, were devastated.

“It was very, very hard on her,” Walter said. “You don’t expect to outlive your children.”

The elder Whitehill died in 1972 from a heart condition. Mary Whitehill, an accomplished artist who designed her own Christmas cards, lived another 44 years after burying her firstborn. She died in 2012. She was 92.

The toughest times for the Whitehill family are David’s birthday and the anniversary of his death. They take some comfort in knowing he died a hero.

He was awarded the Purple Heart, the Distinguished Flying Cross, Air Medal and New York State Conspicuous Service Cross.

Whitehill would have celebrated his 50th ReUnion in June. Instead, he rests next to his parents in the family plot at Cedar Hill Cemetery in Middlehope, N.Y.

“He felt it was a part of his service,” Walter said of his brother’s decision to enlist in the Air Force while at Union. “He gave up his life for his country.”

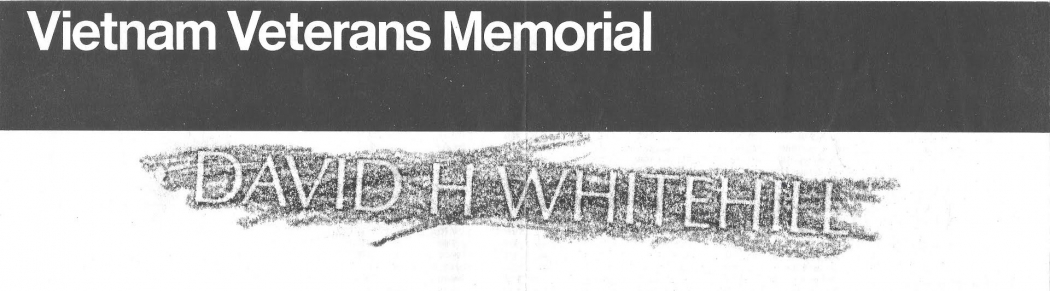

The name of David H. Whitehill '66 on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C.