It was just before dawn on a summer Sunday morning when a loud, steady hum emanated from Drew Lentz’s metal detector. The campus was nearly deserted and Lentz was surveying a grassy hill yards from the President’s House.

He bent down and gently sifted through the soft soil. He noticed the object buried about seven inches in the ground. It was not a quarter as he initially believed. A silver chain was partially exposed. He tugged on the chain and lifted it from the ground.

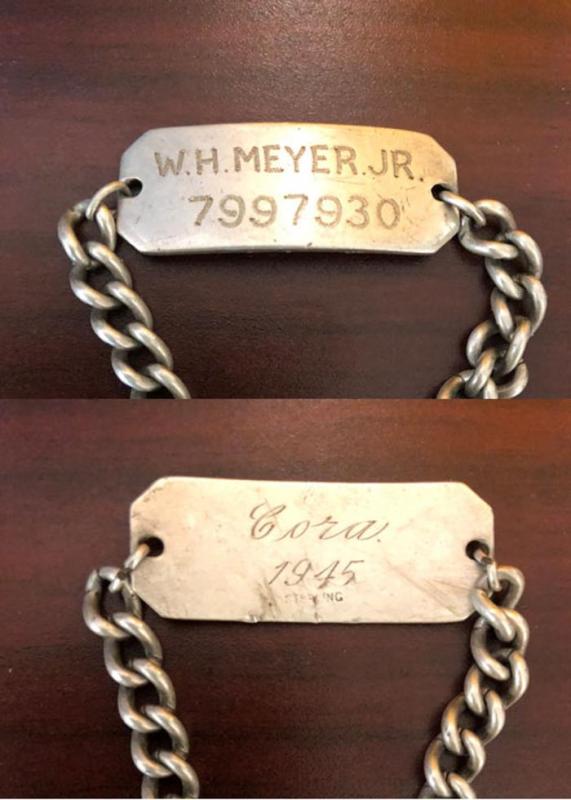

Shaking off the dirt, Lentz could now see what he had uncovered: a military identification bracelet.

“It was a shock,” said Lentz, the assistant registrar. He has been metal detecting for 25 years, discovering numerous coins, artifacts and other items on campus. All are turned over to Special Collections.

The front of the sterling silver bracelet was engraved “W.H. MEYER JR” and a serial number: 7997930.

The other side was inscribed in cursive: “Cora 1945.”

The discovery of the bracelet buried on campus for nearly 70 years raised an intriguing question: what became of the couple whose names were inscribed on the jewelry?

Some quick research confirmed the basic narrative of the bracelet’s origins.

“W.H. MEYER JR” was William Henry Meyer ’48. Born in Schenectady, Meyer entered Union after graduating from Poughkeepsie High School in 1944. The son of William, Class of 1928, he played varsity lacrosse and was a member of Sigma Chi. He directed the band, which played at most football games “not only the usual repertoire of college songs and standard marches, but also a good share of novelty numbers and fancy formations,” according to The Garnet.

“Cora 1945” was Cora Barnes. Like Meyer, she grew up in Poughkeepsie. The two had shared the stage from an early age. In 1934, when they were seven, they performed in the Christmas pageant at the Reformed Church. William was one of the Wise Men, Cora, a mother. At Poughkeepsie High, Cora was the assistant director of the school’s production of “Watch on the Rhine;” William was in charge of the curtain.

William was clearly smitten with Cora. They started dating in high school. When he went off to Union and she to New Paltz State Teachers’ College, the relationship continued.

At Union, William escorted Cora to dances hosted at the fraternity. One, in November 1946, was noted in a roundup of students and their dates in The Concordiensis with the headline “And the moonlight beams on the girl of my dreams.”

The bracelet celebrated their love.

In February 1945, Meyer took a break from Union to enlist in the Navy. It was then that Cora likely gave her sweetheart the bracelet.

It was common during World War II for loved ones to give their boyfriends or spouses an ID bracelet. The jewelry was both personal and practical. It represented a token of affection. It was also helpful if the recipient was wounded or killed in action.

Meyer returned to Union after a year as a pharmacist’s mate. A pre-med student, he graduated with a degree in biology. At some point during his final years on campus, he apparently dropped the bracelet. The grassy knoll where it was found, with its tall black walnut trees providing shade, was a popular spot for students to hang out back then. The Sigma Chi fraternity house (now Gleason Funeral Home) was directly across the street.

At 2 p.m. on Saturday, June 19, 1948, William and Cora were married by Rev. Franklin J. Hinkamp, minister of the Reformed Church in Poughkeepsie. This time, a ring was the chosen jewelry.

After Albany Medical School, William completed his internship at Jackson Memorial Hospital in Miami, Fla. and residency at the University of Miami Medical School. He eventually opened a practice in vascular surgery in Fort Pierce. He served as chief of surgery at several Florida hospitals, was past president of the Florida Association of General Surgeons and authored a dozen scientific papers.

Cora, a school teacher, helped William in his practice and was co-owner of a boutique shop, the Bikini Racquet, in Fort Pierce, Fla.

The couple had three children: Susan, Scott and Todd. Scott was killed in 1985 when a private plane he was a passenger in crashed in a swamp near Fort Pierce during a thunderstorm.

William retired in 2002.

“They were fortunate enough to travel the world together,” says their son, Todd.

The mystery of how the bracelet may have slipped from William’s grasp may never be known.

In the summer of 2016, William suffered a stroke. He died in November, less than a year before Lentz found the bracelet. He was 89.

Cora is 92 and lives in a nursing home in Port St. Lucie, Fla. The bracelet was returned to her son, Todd, this past January. He presented it to his mother, who wears it now. In the twilight of her life, dementia has robbed her of its significance.

This June, William Meyer and Cora Barnes would have celebrated their 70th wedding anniversary. Who knew they would share a lifetime of memories stretched across the same decades as that special token of their enduring love?

Finally, the bracelet once exchanged between two young lovers has found its way home.