Depression, PTSD, substance use disorder, Alzheimer’s. Different conditions, often affecting very different people. But these diseases have something in common.

Psychedelic drugs might help treat them all.

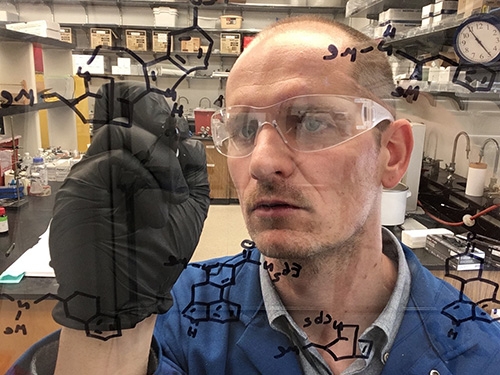

“Many neuropsychiatric diseases, including these, are characterized by cortical atrophy – the physical withering of neurons in a part of the brain that controls fear, motivation and reward,” said chemist and neuroscientist David Olson ’06. “Our research group found that psychedelics are particularly good at re-growing these key neurons, and I believe their ability to directly address this root cause of many neuropsychiatric diseases is why they hold so much promise for improving mental health.”

Olson conducts his research at the University of California, Davis, where he is an associate professor in the departments of Chemistry and Biochemistry & Molecular Medicine. He is also involved in this work through a start-up he co-founded called Delix Therapeutics.

“My lab studies classic psychedelics like LSD, DMT and psilocybin; entactogens like MDMA; atypical psychedelics like ibogaine and salvinorin A; dissociatives like ketamine; and deliriants like scopolamine,” explained Olson, who is the chief innovation officer and head of the scientific advisory board at Delix. “Though many of these molecules might demonstrate efficacy for treating similar diseases, each compound has unique characteristics that make it better suited for one application over another.”

“For example, ketamine was recently approved for treatment-resistant depression, while phase 3 clinical trials have demonstrated that MDMA may be effective for treating PTSD,” he added. “Psychedelics represent a step toward actual cures for neuropsychiatric diseases instead of drugs that simply mitigate disease symptoms. As another example, a patient with depression may find their anhedonia is relieved after undergoing psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy.”

Despite this promising and exciting potential, treating people with psychedelics is very challenging. These powerful compounds come with powerful side effects, the most obvious one being hallucinations.

“The hallucinogenic effects of these drugs necessitate in-clinic administration under the supervision of a healthcare professional. And psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy is contraindicated for people with disorders like schizophrenia,” Olson said. “As a result, I think treatment will only be available to a limited number of patients.”

Unless, that is, somebody takes the trip out of the treatment.

And that’s just what Olson is trying to do.

“My academic lab and Delix Therapeutics are developing non-hallucinogenic compounds that promote cortical neuron growth and heal damaged neural circuitry,” he said. “Our goal is to produce medicines that are safe enough that you can pick them up from your local pharmacy, take them home and store them in your medicine cabinet.”

Some structural features of psychedelic molecules enable them to promote synaptogenesis (neuron growth). Others are responsible for hallucinations. “We simply build new molecules that have features conducive to producing synaptogenesis but not hallucinations,” Olson explained.

“Finding new medicines for treating brain disorders should be deeply personal to everyone. Approximately one in five people will suffer from a brain disorder at some point in their lifetime,” Olson said. “We all know at least five people, so chances are that you or someone you care about has been impacted by these illnesses.”

Olson majored in chemistry and minored in biology at Union before earning a Ph.D. in chemistry from Stanford University. He did postdoctoral training in neuroscience at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard University.

Olson credits his career path, in part, to Joanne Kehlbeck, professor and chair of Union’s Chemistry Department.

“My undergraduate experience at Union had an enormous impact on my career trajectory,” he said. “My mentor, Joanne Kehlbeck, really inspired me to pursue scientific questions at the interface of chemistry and biology. Without her advice and guidance, I wouldn’t be where I am today.”