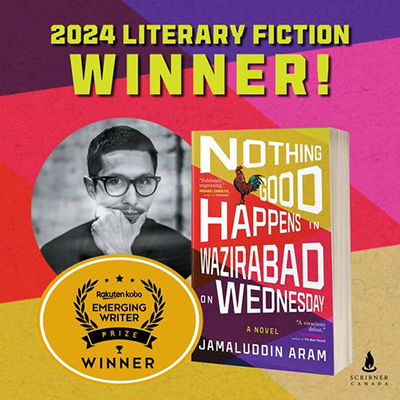

Jamaluddin Aram ’17 has won the 2024 Rakuten Kobo Emerging Writer Prize for Literary Fiction for his debut novel, “Nothing Good Happens in Wazirabad on Wednesday.” The book was released by Scribner Canada last summer.

The annual $10,000 award recognizes the year’s best debut books by Canadian writers in nonfiction, literary fiction and mystery. Each winner also receives promotional support from Kobo, a Canadian company that sells e-books and related accessories. The company aims to make reading accessible to everyone in the belief that stories can change the world.

Aram, of Kabul, Afghanistan, resides in Toronto. An English and history major at Union, he has penned short stories and essays focused on themes of family, immigration, childhood and peace in a time of war in his native city and country.

“Nothing Good Happens in Wazirabad on Wednesday” is set in Kabul, Afghanistan in the 1990s. The book draws upon his childhood, showcasing everyday life in the winding alleys of the working class neighborhood of Wazirabad through an assortment of characters: a bonesetter who reads classic poetry to his cat, a drunk electrician, and a small girl who learns to earn money by making calligraphy on kites and selling scorpions to keep her mother from having to sell herself to the soldiers.

In accepting the Kobo award, Aram quoted William Faulkner’s learned belief from Sherwood Anderson that “to be a writer, one has first got to be what he is, what he was born.”

“I was born a Hazara, an Ismaili, a Shiite, a Muslim… I grew up in Kabul, so did my parents, but my grandparents came from Bamyan, the central highlands, where the mountains are as old as time itself. In those altitudes barely anything grows, but hope. The air burns the lungs and the sun has yet to learn to kiss the skin, it tears into it,” Aram said.

His grandparents looked for opportunities in Kabul, but as Hazaras, “they were a people stripped of their humanity by those in power. They worked jobs others wouldn’t touch, lived in rental rooms that half the year filled with water, so they had to sleep on wooden decks raised on stilts.”

Aram’s parents eventually were able to build a house, raise their family in it and send their children to school.

In acknowledging the grinding poverty, the gender apartheid, and the political oppression underway in his country of origin, Aram laments the world’s lack of attention and lost interest. He asks, “Why have all the camera lenses turned away? Is there a right way to suffer and we, the people of Afghanistan, are doing it wrong?”

As a writer, Aram said, “I feel a moral responsibility toward people whose stories constantly had to give way to narratives that were deemed more important. So their sufferings, joys, failures and achievements went unnoticed because they belonged to a certain social class.”

Still, he maintained there was “no time for despair. It is time for hope, for kindness, for light. It is time to write: unapologetically, without compromise or exaggeration, without accusation or self-pity; it is time to remember and to write about who you are and what you were born; it is time to write honestly and proudly and well and beautifully. For in our times, writing, like breathing, is a political act.”

In addition to receiving the Kobo fiction prize, Aram has garnered other recognition. In 2020, he was named one of three finalists for the Bronwen Wallace Award for Emerging Writers in the short fiction category for his story, “This Hard Easy Life.”