In 1824, physician, botanist and geologist Lewis C. Beck published an article in the New York Medical and Physical Journal on research he had done on the climate of the valley of the Mississippi.

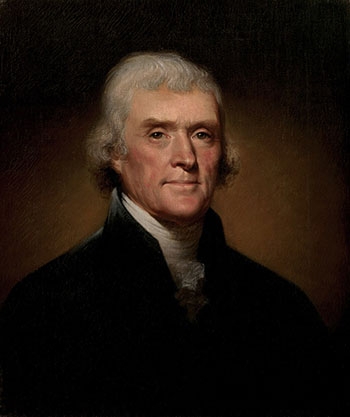

A member of Union’s Class of 1817, Beck challenged a theory on climate offered by Thomas Jefferson of both his home state and America as a whole in his 1787 book, “Notes on the State of Virginia.” Jefferson believed that, at similar parallels of latitude, the climate of the Mississippi Valley was warmer than that of the Atlantic Coast.

A gentleman farmer, Jefferson was fascinated with weather. In fact, as he was completing work on the Declaration of Independence, Jefferson began keeping a temperature diary. For the next 50 years, he would take two readings a day and scrutinize the numbers to determine a connection between human activity and rising temperature readings.

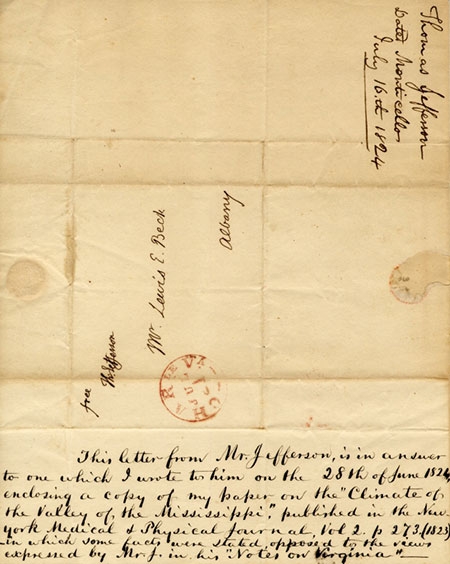

On June 28, 1824, Beck mailed a copy of his article to the former president. A couple of weeks later, Jefferson replied.

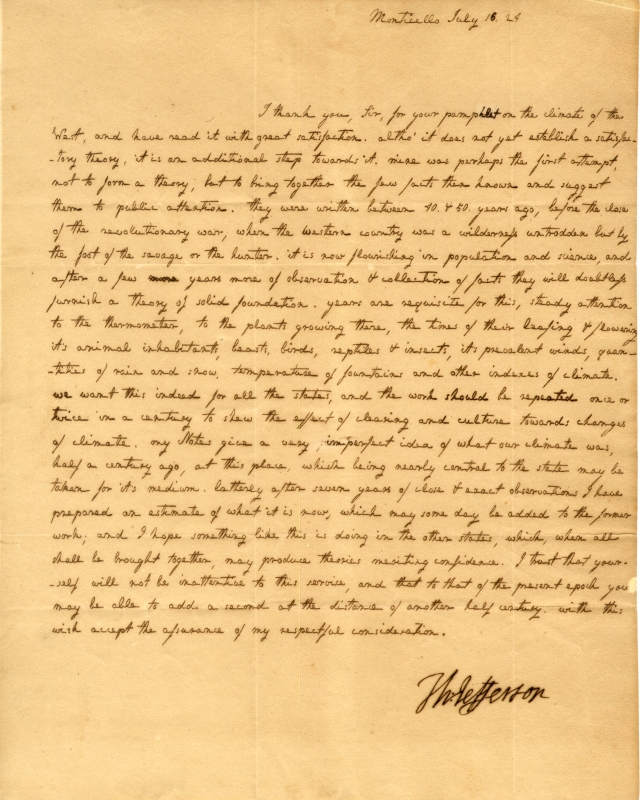

“I thank you, Sir, for your pamphlet on the climate of the West, and have read it with great satisfaction, altho it does not yet establish a satisfactory theory, it is an additional step towards it,” read the letter dated July 16, 1824, and sent from his home in Monticello, Va.

The handwritten letter from Jefferson to Beck is among several letters with presidential connections housed in Special Collections and Archives.

All of the letters are part of a project completed during the fall term. Six student assistants examined and inventoried each of the collection's approximately 18,000 letters that date from the mid-1700s to the 1970s. The file includes crucial Union records from college presidents, treasurers, registrars, and other prominent figures.

There’s a March 18, 1938, typewritten letter on White House stationery from President Franklin Delano Roosevelt to Dixon Ryan Fox, Union’s 12th president. Roosevelt politely declines Fox’s request for a special postage stamp to coincide with a celebration of Sir William Johnson, a prominent figure in the French and Indian War.

Months after leaving office as president, Grover Cleveland wrote a handwritten letter May 13, 1897, to Andrew Van Vranken Raymond, Union’s ninth president. Cleveland offered his regrets for an invitation to be commencement speaker in June because he would be starting his vacation.

There are also two letters to Raymond from New York Governor Theodore Roosevelt shortly before he became president: one invites Raymond to the governor’s residence in Albany for lunch, and the other thanks Raymond for having a distinct influence on Roosevelt.

Naturally, there is plenty of correspondence from Chester A. Arthur, Class of 1848, who rose to become the country’s 21st president. And a handful of letters from the recently deceased Jimmy Carter, the nation’s 39th president. As a young Navy lieutenant, Carter took special non-credit classes in reactor technology and nuclear physics at Union in the spring of 1953.

“We wanted to make sense of what we have in the extensive letter file, and to also make it easier for researchers to discover and access crucial letters from Union's history,” said Joseph Lueck, outreach and reference archivist in Special Collections.

Students who worked on the project include Gabby Baratier '25; Tracy Chen '26; Clare Reilly '26; Robbie Levitt '26; Cole Sanderson '28; and Petr Melnikov '28.

The Jefferson letter offers both a window on the scientific research of a distinguished Union graduate, and a case study of the evolution of the discipline of paleography.

The letter was donated to the College in 1953 by Beck’s family to mark the 100th anniversary of his passing. It was believed at the time of the gift that the letter was in Jefferson’s handwriting, and a ceremony in the library that attracted media attention touted that fact.

However, an appraiser in 1961 determined that the letter, though signed by Jefferson, was in the hand of his daughter, Martha.

Decades later, experts at Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello confirmed to the College that Jefferson’s original draft of the letter to Beck in his handwriting is kept at the Library of Congress. It contains a number of canceled words replaced by interlined substitutions, and is initialed rather than signed by him. Jefferson then had his granddaughter, Ellen Wayles Randolph, not his daughter, copy the letter out cleanly, and he signed and mailed the new version, retaining the draft for his own records.

“This is a departure from his previous practice,” said J. Jefferson Looney, editor and project director for The Papers of Thomas Jefferson: Retirement Series. Since 1999, Looney and his team have spent years indexing thousands of Jefferson’s letters for inclusion in the definitive edition of Jefferson’s post-presidential papers that will contain 24 volumes, published by Princeton University Press. The Beck letter will appear in volume 21, which will come out later this year.

“Until late in his life Jefferson wrote a draft and then prepared a fair copy in his own hand using his polygraph machine. This left him with the original draft, which he usually did not keep, the fair copy, which he sent, and the polygraph copy guided by the second pen in his polygraph machine, which was almost exactly identical to the version sent and which he kept.”

By 1824, however, Looney said the polygraph was no longer in working order. Jefferson was also in failing health.

“While he often still made the fair copy to send, Jefferson sometimes found it necessary to ask relatives, such as Randolph, to assist him by copying the version to be sent, using the draft, which he then retained for his own records,” he said.

A letter from Thomas Jefferson to Lewis Beck, Class of 1817, is among a collection of letters from those with presidential ties in Union's archives.