What liquids might exist in larger ocean worlds, and what do the different possible compositions imply about their interior structures?

That is a question a team of researchers, including Heather Watson, associate professor of physics and astronomy, will explore thanks to a recent $1.9 million grant from NASA.

The group’s answers could eventually help to determine if conditions exist for human life beyond Earth within the solar system.

Led by Steve Vance, an astrobiologist and geophysicist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, the team also includes researchers from the University of Washington, Texas A&M, UCLA and ETH Zurich.

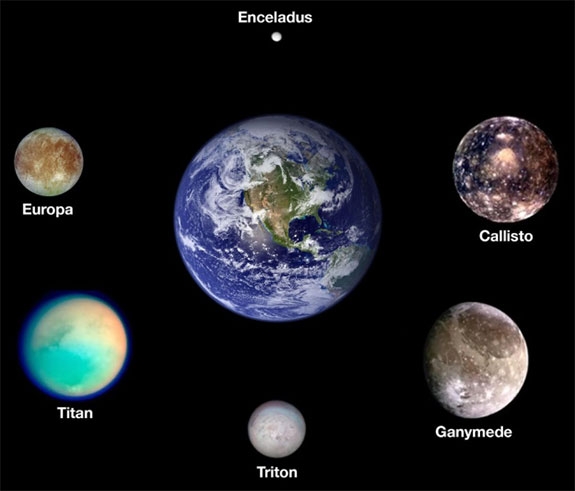

They will investigate the existence, location, and characteristics of liquids and ices in the large ocean worlds of Jupiter (Europa, Ganymede, Callisto) and Saturn (Titan).

Interior models will test how different possible compositions in these worlds control the thicknesses of their ices and oceans for different thermal states and under what conditions fluids might reside under high-pressure ices.

The goal is to develop a further understanding of ocean worlds in the solar system using laboratory experiments and computational modeling.

“Icy worlds like Europa are thought to have salty liquid water oceans under the ice,” said Watson. “Because of this and some other factors, they are important candidates for understanding if and where life can exist beyond the Earth.”

Watson’s main role for the project is to perform liquidus (melting and freezing) experiments on many salt-water solutions of different compositions at high pressures relevant to the icy worlds and to develop preliminary crustal thickness models based on those results.

She credited George Shaw, professor emeritus of geosciences, for his work on a prior NASA proposal that built the main instrumentation in her lab and for collecting preliminary data that made this new project possible.

The project creates valuable research opportunities for up to two students a year to assist Watson for the duration of the four-year grant.

It also comes at an opportune time. Last October, NASA launched a spacecraft, Europa Clipper, to conduct a detailed investigation of Jupiter’s moon Europa to determine whether there are places below its icy surface that could support life.

If all goes well with the mission, the spacecraft will arrive in Jupiter in 2030 after traveling 1.8 billion miles.

“This work will provide laboratory data to help us understand the inner workings of these far away planets and moons and help us interpret information sent back from robotic missions such as the Europa Clipper,” Watson said. “This combined effort, along with others, could be used to eventually determine if the environments within these worlds may be hospitable to extra-terrestrial life.”