Fifty years ago this month, thieves broke a rear window on the ground floor to gain entry to Schaffer Library. They headed to a locked case and smashed the quarter-inch thick glass with a hammer to retrieve the bounty on display for Commencement weekend: a single volume of naturalist John James Audubon’s stunning “Birds of America.”

Measuring over three feet in height and running to four volumes that each weigh more than 40 pounds, “Birds of America” is one of the most celebrated books of natural history. It is also one of the world’s most valuable, worth an estimated $8 million to $12 million today.

Audubon had created about 200 copies of the set, which featured 435 hand-colored prints of 1,037 birds; only 120 sets exist today. Union President Eliphalet Nott paid Audubon $1,000 for a set in 1844. Except for a brief stay in Cooperstown, N.Y. for safekeeping during World War II, the prints have remained on campus as one of the College’s greatest treasures.

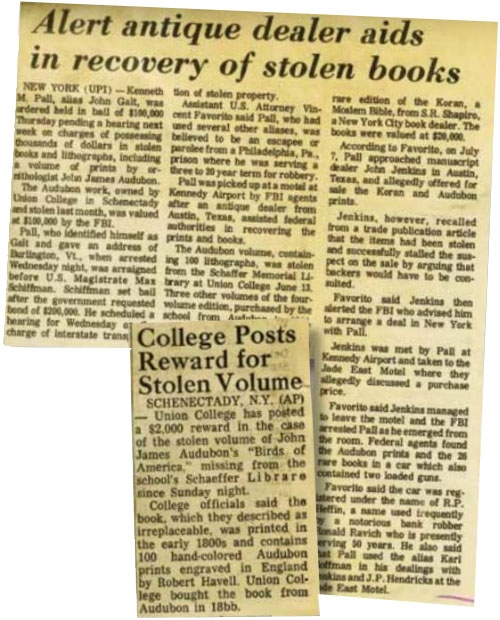

The daring theft in June 1971 generated headlines across the country. It also drew the attention of the FBI. John Holmes Jenkins III, a prominent rare book dealer and publisher from Austin, Texas, alerted the agency to a man he said had wandered into his shop weeks after the theft looking to sell pictures of birds discovered in an attic. To Jenkins, the prints sounded suspiciously like the ones he had seen in a notice about Union’s theft in the weekly Antiquarian Bookman.

Working with the FBI, Jenkins later met with the man at a Queens, N.Y., motel. Federal agents stormed the room. They eventually discovered the stolen Audubon prints, along with a number of rare books taken in a separate robbery in New York City, in the trunk of a 1970 gold Chevrolet Impala used by the suspect.

The cover page of the Audubon folio was missing and several of the plates were torn after being ripped from their binding. Blood stains dotted six of the prints, presumably after the thief cut himself on glass shards from the shattered case.

Lauded as a hero, Jenkins collected a $2,000 reward from Union, which he returned. The College used the money to create a bibliography award in his name. It also awarded him its Founders Day Medal and an honorary degree. He also served briefly as a member of the Board of Trustees.

Jenkins wrote a breathless account of his heroic deed for “Audubon and Other Capers: Confessions of a Texas Bookmaker.” Jenkins loved publicly sharing the story of his role in the recovery of the prints, stating, “It gets a little better each time I tell it.”

For decades, the version offered by Jenkins shaped the narrative of the heist.

It was not until the summer of 2011 that a broader picture of the theft emerged. Taking a fresh look at the heist on its 40th anniversary, the College’s alumni magazine published an exhaustive account that included many new details, including the origins of the crime.

The theft was traced back to a shady Brooklyn book dealer, James S. Rizek, who had done business with both the College and Jenkins. Rizek had served time for defrauding libraries, among his other crimes. He allegedly recruited others to steal the Audubon volume.

Most tellingly, the article included a bombshell claim from Kenneth Paull, the man who met with Jenkins at his shop in Texas in 1971 and was arrested at the Queens motel. A career thief from the Philadelphia area, Paull scoffed at Jenkins’s portrayal as a hero.

“I didn’t know an Audubon from a Schmaudubon,” Paull told the magazine. “I was a professional thief. Do you honestly think I just flew down to Texas and looked around for somebody to buy stolen goods? We did not do anything on spec. We had a customer.”

Paull, 87, is the last remaining character in the ordeal still alive, and his account cannot be corroborated. After a series of conversations with a Union Magazine writer in 2011 about his role, he said he no longer wished to discuss the heist.

Paull’s insistence that Jenkins played a far more sinister role touched off a fierce debate. Many who had done business with Jenkins found it plausible that he exaggerated and even grossly misrepresented his role in the recovery.

Wayne Somers '61, editor of the Encyclopedia of Union College History, worked at the library at the time of the theft. He has a different view.

“Because John Jenkins was pretty clearly guilty of several crimes, it's tempting to add his role in the Audubon affair to the list, giving a sinister spin to his later fictions,” said Somers. “But the vagueness of the phrase 'in on it' makes such a charge tendentious at best. Whatever 'in on it' may mean, Jenkins could have been 'in on it' only if the crooks wanted him to be, and they had every reason to want Jenkins to know nothing. Letting Jenkins know Rizek was involved would put Rizek's parole at risk, and letting him know the goods were stolen would devalue them. Nor was there any advantage to them in Jenkins knowing those things.”

Jenkins died in April 1989. His body was found floating in the Colorado River near Austin with a gunshot wound in the back of his head. A renowned poker player, he was deeply in debt, and some believed he was about to be indicted for setting fires to his warehouses to collect the insurance money. Even his death was murky. A justice of the peace ruled it a homicide; the county sheriff insisted Jenkins committed suicide to escape the troubles piling up his life.

More than 30 years after his death, there was renewed public scrutiny of Jenkins. In March 2020, Texas Monthly published a lengthy piece, “The Legend of John Holmes Jenkins,” which recounted some of his alleged misdeeds, including forgery and arson.

A more damning account of his life was the release the following month of “Bluffing Texas Style: The Arsons, Forgeries, and High Stakes Poker Capers of Rare Book Dealer Johnny Jenkins,” by Michel Vinson, a book dealer and one-time acquaintance of Jenkins.

Writing in the Wall Street Journal, a reviewer said, “Mr. Vinson has solved the longstanding mystery of Johnny Jenkins. His research shows that, beginning with his college days, there was never a time when Jenkins was not cheating, swindling, stealing and lying.”

Vinson devoted nearly a full chapter to the Union heist, relying heavily on the 2011 alumni magazine article. He also shared new information that may explain in part Jenkins’s motivation in getting tangled up in Union’s crime.

Months before the heist, Jenkins had been rejected for membership in the prestigious Antiquarian Booksellers Association of America, purportedly because of questions about his character. As someone who loved the limelight, he was stung by the rejection.

“If he could save the Audubon plates by turning on the crooks who thought he would be their fence, then he could recast his reputation,” said Vinson. “And that is exactly what happened. He was admitted to the association in 1972, was elected to the Board of Governors in 1975 and became president of the organization in 1980. No one ever learned that he was the original fence who was supposed to buy the stolen Audubon plates.”

No one was prosecuted for Union’s crime. That likely would not be the case today, said Geoff Kelly, a special agent with the FBI in Boston and a member of the bureau’s art crime team.

Formed in 2005 in part to track down antiquities that were looted from the Baghdad Museum after the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq, the art crime team has recovered nearly 15,000 objects worth nearly $800 million and secured more than 90 convictions.

Federal statutes back in the 1970s did not have much meat on them to aggressively prosecute for interstate transportation of stolen property.

Referring to the Audubons, he said there is often a misconception about art theft.

“It’s not like ‘The Thomas Crown Affair,’” said Kelly. He is the lead investigator for the infamous Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum heist, the largest theft from a museum in modern history. He was also involved in the high-profile investigation into the theft of quarterback Tom Brady’s game-worn jerseys in Super Bowls LI and XLIX.

“It is usually con men, criminals, bank robbers who do these things,” he said.

Fifty years after the dramatic Audubon theft, a definitive account remains elusive. Answers to key questions may forever stay a mystery.

Today, Union’s Audubon set looks better than ever. As part of a restoration project in 2006, each lithograph was removed from the four bound volumes, cleaned, mended and placed in special archival boxes. Individual plates are displayed periodically in a highly secure case in the Lally Reading Room in Schaffer Library.

Carl George, professor emeritus of biology, arrived at Union in 1967. From the moment he first viewed the Audubon folios, he has been inspired by their beauty and attention to detail. He was the first professor at the College to use them as a teaching tool for his students. Now 90, he continues to give presentations on the prints.

“Art and science are not that distant, and the Audubons are a great combination of science and art,” said George. “A good scientist is often times a fine artist, and an artist is often times a fine scientist. The Audubons speak to Union’s mission of uniting the different disciplines.”